- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Visitor Regulations

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Exploring Ceramics - Víctor Alfaro: "Learning from art expands the mind"

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

The Use of Spondylus Shells in Moche Ceremonial Contexts: Why Were They Symbols of Status and Wealth? ...

El Brujo Celebrated International Museum Day with Its Community: A Day of Encounter and Cultural Co-Creation ...

To receive new news.

Por: Katerine Albornoz

By Katerine Albornoz

Introduction

There are different material media that were used as a means of artistic, cultural and social expression. Moreover, their study allows researchers to approach a better understanding of the knowledge that each of the societies possessed. Ceramics, also known as pottery, is among the main vestiges left by our ancestors. Therefore, this note aims to explain what ceramics consist in, its importance and the process of crafting it by the hand of a plastic artist.

Between ceramics and pottery

Ceramic production in the pre-Hispanic world –pottery– is the result of a knowledge set transmitted by a society in a certain geographical context (Mannoni & Giannichedda, 2004). This is how researchers resort to their study with different objectives, be it to understand their production dynamics, manufacturing techniques, distribution networks or decorative styles, among others (Bernier, 2009; Gamarra & Gayoso, 2008; Ramon, 2013).

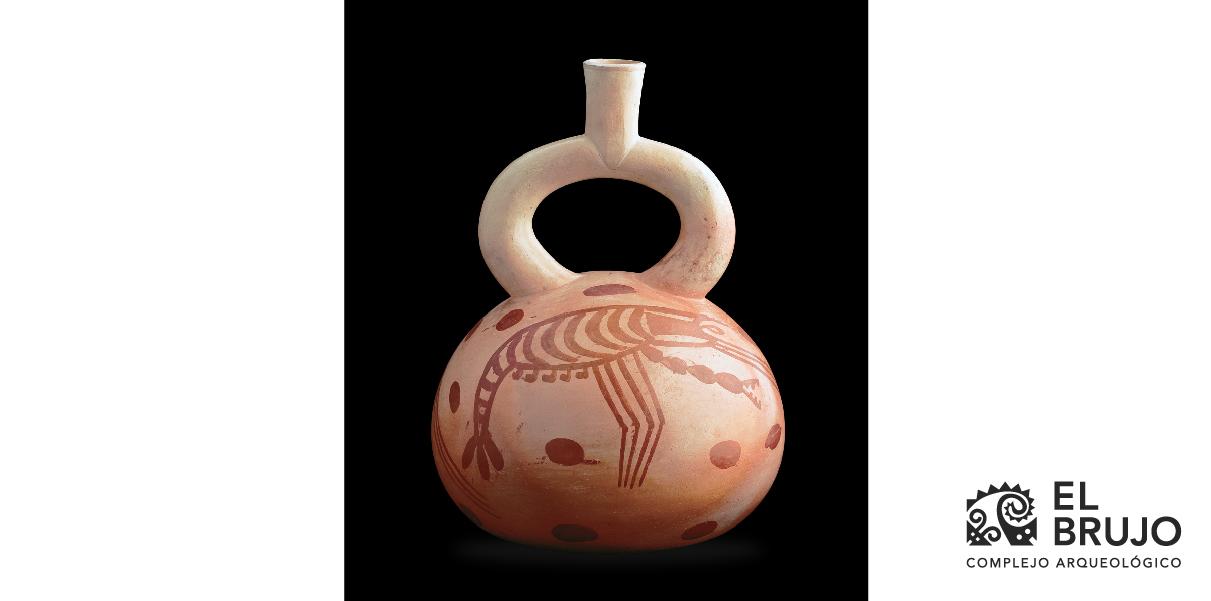

Figure 1. Globular bottle decorated with two shrimp. Source Mujica, 2013

In order to obtain a piece of ceramic –an object made of baked clay (Figure 1)– it must go through a series of previous steps, what we could call the elaboration process. The first thing to do is to obtain the raw material, clay, which is mixed with water. The next step is to give it the desired shape and, for this, we have modeling techniques. Then, the finishing is done on the surface (smoothing, polishing, burnishing, scrubbing) to move on to the decoration stage. Subsequently, the piece is left to dry and then proceed to bake it (Cruz, 2008; Manrique, 2001).

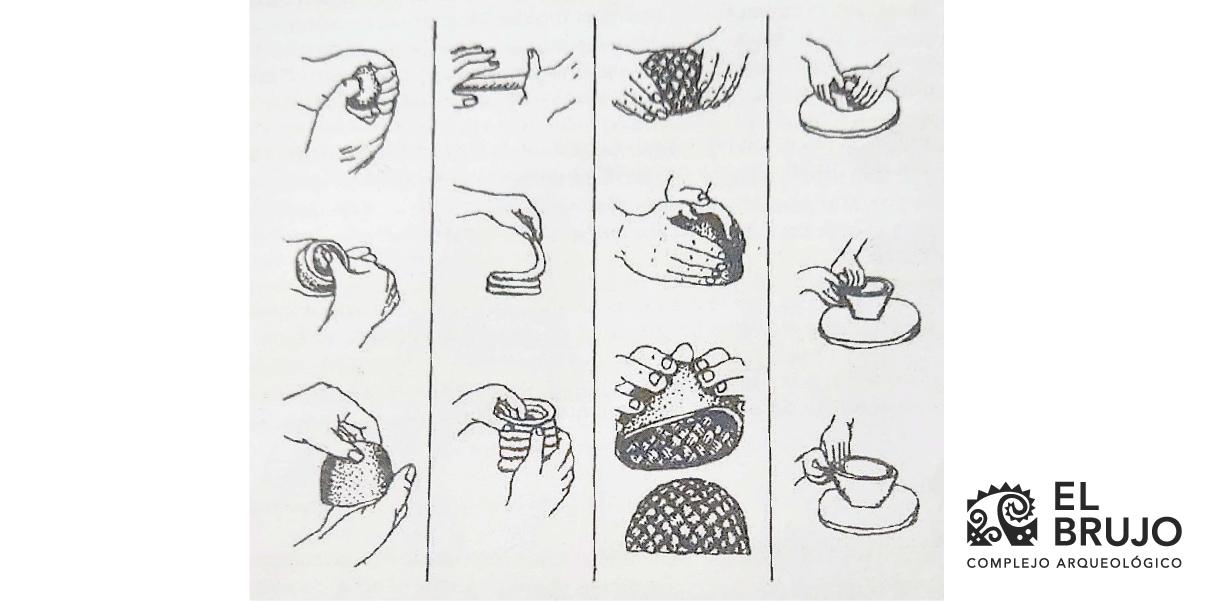

Image 2. Manufacturing techniques (Ruiz, 1988)

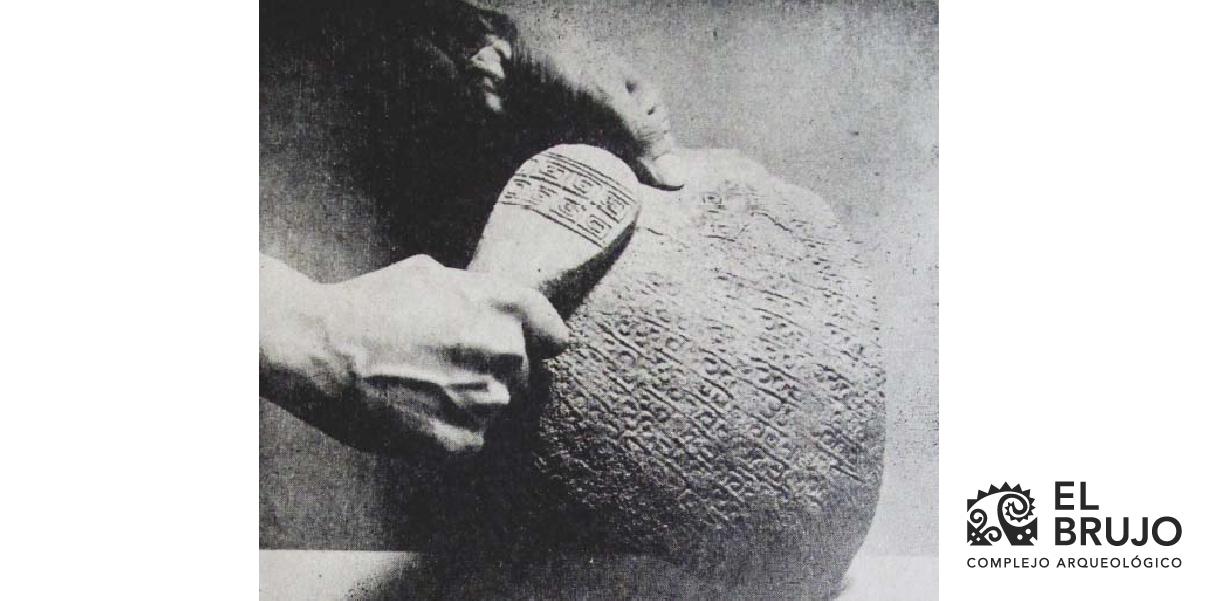

Among the best-known ceramic manufacturing or crafting techniques are: hollowing, molding, modeling and rolling (Mirambell, 2005) (Figure 2). As for the decorative techniques, there is a record of the following: paddling, painting, stippling, stamping, among others (Kroeber & Muelle, 1942; Mirambell, 2005) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Paddling technique (Kroeber & Muelle, 1942)

The arrival of the Spaniards introduced new technologies, such as the lathe (Acuña, 2010), and in recent years new techniques and materials have been used to make a piece of ceramic. However, the practice of pottery still persists in some communities where the use of their traditional tools and techniques is preserved (Druc, 2009; Lara & Ramón, 2020; Roa et al., 2021).

The endeavor of the pre-Hispanic and current potters shows different characteristics as a product of the social, cultural and temporal context in which they have developed. Despite the above, there are traits that have been maintained over the years, such as the knowledge of manufacturing or decorative techniques, which are transmitted to the new generations by the same community, family, schools, among others. As a complement, the work of the potter/ceramist integrates the social and cultural identity of a society (Gonzales, 2017; Patiño & Garzón, n.d.).

A conversation with the ceramist

Nowadays, this activity is developed in different communities both in a non-traditional and a traditional way. To learn more about this endeavor in the present time, we had a conversation with Mr. Víctor Alfaro, a native of the district of Paiján.

In the interview with Mr. Victor, he tells us about his interest in promoting art and culture in Paiján and the relationship with ceramics.

Photo. Víctor Alfaro explaining about the crafting of a piece of ceramic

KA: How did your interest in art and ceramics start?

VA. In my family, both my maternal and paternal grandmothers did manual crafts, ethnic handicrafts and crocheting. I was always connected to handicraft activities. When I was in high school, there was a carpentry workshop and when I graduated I looked for a carpentry shop in the area to start working, especially finishings and painting. The owner of the carpentry shop is a carver and I liked it when he made the images on the doors. One day, I asked him where I could learn to carve and he told me about the School of Fine Arts. I took some summer courses in Trujillo and liked the experience, so I applied to the School of Fine Arts. I believe that studying art expands the mind. I learned about painting, sculpture, pottery, and various subjects that have helped me to develop. Shortly after graduating, I started working in painting and pottery, and since then I have been practicing and teaching this art to children.

KA: What difference do you see between the traditional and non-traditional ways of making ceramics?

VA. The main difference would be the techniques that we use to make a piece of ceramic and the use of the oven for the baking process. At the School of Fine Arts we learned traditional and non-traditional techniques. Particularly when I make pieces on request, I use the lathe and the baking is done with a traditional oven. For this, I must dig a small hole in the ground and use leftover branches as burning material.

Final thoughts

Craftsmanship in different fields –textiles, sculpture, painting, etc.– requires a knowledge set that the artisan applies for its realization. In our pre-Hispanic, colonial and republican past, studied by different researchers, and in the present time, that knowledge set has an intrinsic value as well as initiatives to be shared through classes, videos, experiential experiences and research, that allow their recording, continuity and preservation.

Bibliography

-

- Acuña, S. R. (2010, July). Traditional Peruvian ceramics. Handicrafts of America, 26–51.

- Bernier, H. (2009). The specialized production of Mochica domestic and ritual ceramics. Estudios Atacameños, 37, 157–178. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31516399010

- Cruz, II. (2008). Technological, morphological and decorative study of Recuay ceremonial ceramics [Bachelor thesis]. Universidad Nacional de Trujillo.

- Druc, I. (2009). Pottery traditions, social identity and the concept of late ethnic groups in Conchucos, Ancash, Peru. Bulletin of the French Institute of Andean Studies, 38, 87–106.

- Gamarra, N., & Gayoso, H. (2008). Domestic ceramics in Moche Huacas: an attempt at typology and serialization. In L. Castillo, H. Bernier, G. Lockard, & J. Rucabado (Eds.), Mochica Archeology. New Approaches (p. 187). Editorial Fund of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

- Gonzales, K. (2017). Shaping identity in the pottery workshops of San Juan de Oriente. Revista Torreón Universitario, 43–58. www.faremcarazo.unan.edu.ni

- Kroeber, A., & Muelle, J. (1942). Paddled Ceramics from Lambayeque. Revista Del Museo Nacional, I.

- Lara, C., & Ramón, G. (2020). Pottery-related ethnography and Andean archaeology. Bulletin of the French Institute of Andean Studies, 49. https://doi.org/10.4000/bifea.11479

- Mannoni, T., & Giannichedda, E. (2004). Archaeology of Production. Ariel Spain.

- Manrique, E. (2001). Guide to a study and treatment of ceramics.

- Mirambell, L. (2005). Pottery/Ceramics. In Archaeological materials: Technology and Raw material. National Institute of Anthropology and History.

- Patiño, L., & Garzón, C. (n.d.). Talavera ceramics as an artisan cultural practice: between the ancestral and the new artistic hybridisms.

- Ramón, G. (2013). The swallow potters. Itinerant producers in the Andes (Primera). French Institute of Andean Studies.

- Roa, A., Durán, R., & Artesanías de Colombia S.A. (2021). Pottery of the Cross - Nariño. In National Reference of pottery and ceramics.

Researchers , outstanding news